It’s difficult to say when and where the concept of “business” was borne. It’s often attributed to ancient Roman law and to British law in the early 1500’s. The Dutch East India Company, established in 1602 in modern-day Jakarta, is often viewed as the first multi-national company and the first company to issue stock. In the U.S., business as we know it today was arguably developed at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

Regardless of when the concept of business was formed, it’s pretty evident that every business—without exception—has always been established to provide a good or service to a customer. Which means we’ve been serving customers for at least four centuries and likely far longer. So why is obtaining and considering the voice of the customer—a business’s raison d’etre—monumentally difficult for so many?

The #1 goal in the Lean management approach is to provide greater value to customers. Adding value is accomplished through a variety of means: better product design, better pricing, less operational waste, faster delivery, better quality, better post-sales service (often more important than the product itself), and so on. But, as I described in my recent book, The Outstanding Organization, businesses must gain impeccable clarity about who their customers are and what they value. In other words, what—very specifically—are their needs and preferences? It is only by doing the heavy lifting to answer this core question that businesses have any chance at all of providing greater value and, therefore, becoming a Lean enterprise.

For the sake of brevity, I’ll skip the part about defining who one’s customers are. (But skipping the topic doesn’t diminish its importance. Some businesses are extremely clear, while others are shockingly unaware who they’re actually serving. More about this in my book.)

Time and time again when I work with clients, I find that even leaders who oversee customer service have difficulty answering basic questions about what their customers value. Why? I’ve found the answers fall into seven buckets:

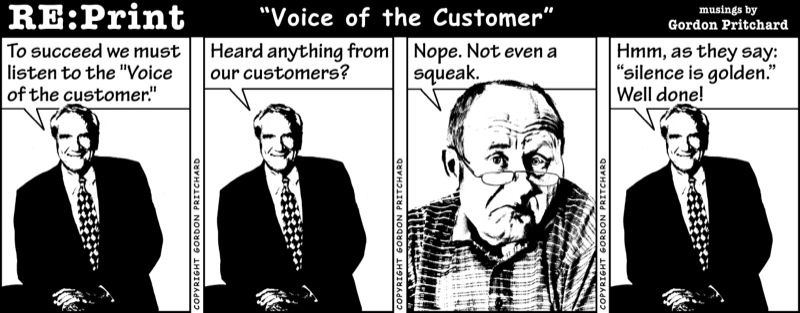

The comic strip below (shared with permission from Gordon Pritchard) describes a shockingly common problem that typically stems from lack of interest, lack of time, fear of the truth, or lack of skill. But there’s zero chance of achieving any level of excellence if you don’t ask. Don’t ask, don’t tell, doesn’t work in life and it doesn’t work in business.

While surveys (of any sort) provide an efficient means to gather data from large numbers of people, there’s a big difference between data and information, and effectiveness trumps efficiency any day of the week. The biggest problem with surveys is that data interpretation and the resulting conclusions depend on sound surveys and survey processes to begin with—a requirement that is shockingly difficult to achieve.

Getting to know one’s customers is best done in their environment, as they’re interfacing with an organization’s goods or services. Gaining a deep understanding about variation in needs and preferences is best achieved by observation and conversation, neither one of which can be accomplished via surveys. I like the term “thick data” (as opposed to “big data”), which I just learned while reading a well-written piece on the subject of qualitative data in this weekend’s Wall Street Journal.

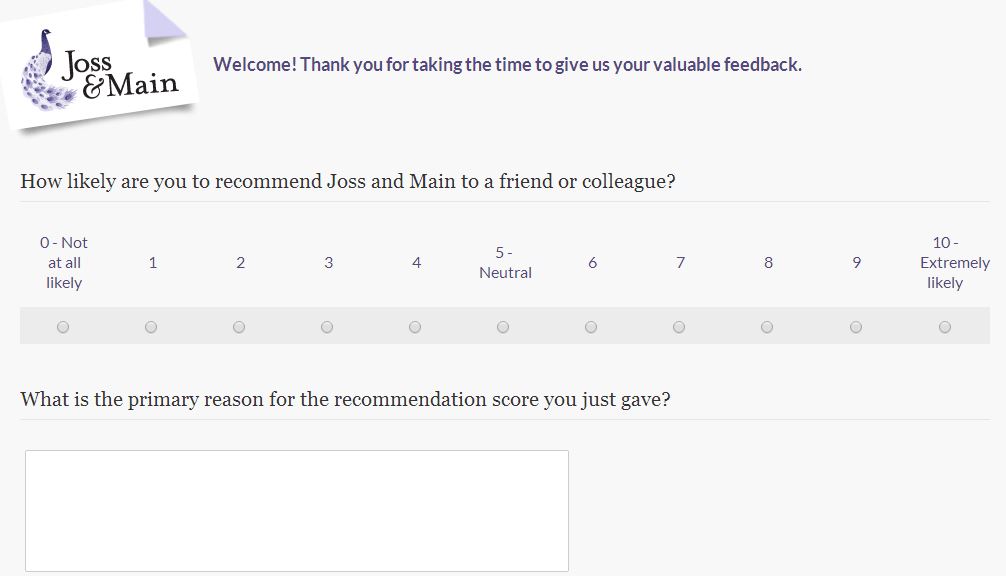

Yesterday I received three customer surveys. Two of them were the wildly popular and, in my opinion, woefully ineffective Net Promoter Score (NPS) surveys that presumably measure customer loyalty:

I’ve long questioned the cause-and-effect conclusion where recommendations necessarily translate into long-term customer loyalty. The minute a better product comes along, customers flock to those products, so today’s success isn’t necessarily a good predictor of future success.

Even worse, customer loyalty today isn’t necessarily a strong indicator that organizations are providing high value. I’ve interfaced with many organizations who receive decent NPS scores, but have significant operational problems that frustrate customers. In nearly every case, their NPS scores provided a false sense of security to senior leaders and slowed the desire for and pace of improvement. I’m not the only one with concerns. In response to one of my Tweets yesterday, Mark Graban shared a well-written analysis.

Don’t get me wrong. I like the simplicity of a single-question survey. But if improving the customer experience is your goal, the single question should some variation of: “What can we do better that would improve your experience?”

The answers to this question provide actionable information (which NPS lacks) and gets far closer to truly understanding customer value. The “downside”: You need to actually do something with the answers or your customers will quickly catch on that you’re merely checking a box and have no real interest in what they think.

UPDATED 4/27/2014:

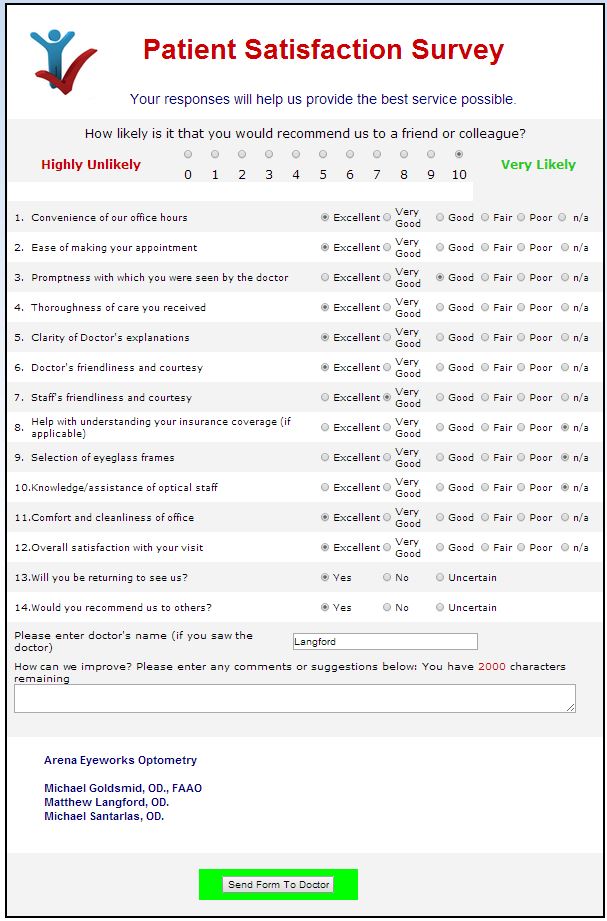

Since I’m hyper critical of most of the customer surveys I receive, I thought I’d share an outstanding one I just received from my eye doctor. This survey shines due to its:

If I get another automated pop-up asking me to complete a customer survey, I’m going to scream. While it’s good news that seeking customer feedback is on the rise, it’s both lazy and disrespectful to program in a pop-up survey with every single interaction a customer has with a business. Nor is it wise to send an email with a survey link after each and every order a customer places.

At best, survey overkill breeds cynicism (“they don’t really care about me”) and at worse it erodes the customer experience. Plus, this practice often gives skewed results that are based on someone’s tolerance level for the intrusion versus reflecting their actual customer experience.

You either want to know the truth or you don’t. Companies that attempt to influence their ratings are better off not asking for feedback at all. It’s insulting to a customer and the resulting data may bear little resemblance to reality.

Influencing takes form in many ways from overt face-to-face begging (“please, our store will look better if you rate us a 5”) to more subtle means such as timing a survey shortly after a “good news” event.

Whether unintentional or not, pre-selecting highest ratings is a form of influencing that can cloud the truth as I experienced yesterday with Delta’s onboard survey, pictured below. If organizations don’t want the unvarnished truth, they should stop wasting their customers’ time.

Drawing the wrong conclusions, which can lead to poor decisions, is the greatest risk with quantitative data. A good example appears in the Lego story in the Wall Street Journal article I mentioned above. Only when Lego took the time and effort to truly get to know its customers did their business turn around. The information was clear, which resulted in better decisions, which led to better results.

When you go the gemba (the real place—in this case, to the customer) and talk and observe, you get far richer information that even a well-written, well-administered survey can yield. Does it take more time and effort? Yes. But as I asserted earlier, effectiveness trumps efficiency. If you want to get to know your customers and what they truly value, talking with them directly is the only way. Aim for getting “thick data” over “big data.”

(Note: For efficiency’s sake, email is a viable option as long as you ask well-constructed open-ended questions, you carefully analyze their responses, and you ask follow-up questions to clarify, if needed.)

It’s a silly practice but, you’re right, many do it. My view: don’t ask questions if you don’t want truthful answers. Thanks for sharing this. Let’s keep raising this issue until the message is heard and orgs take appropriate action. Surfacing problems is the only way to success!

I think many organizations don’t want honest answers, they want good scores!

You got that right! Reminds me of Jack Nicholson in A Few Good Men… :-)

Great insights, thanks for sharing. I’ve been working with businesses teaching the lean startup process for about a year now and find that your points on not asking the right questions or trying to influence the answers are two of the hardest hurdles for well meaning entrepreneurs to overcome. There seems to be a need to develop skills for meaningful inquiry!

Ariana – thank you for sharing your experience. Yes, it seems that what comes very naturally to some doesn’t come naturally to all. And while I think having a strong emphasis on voice of the customer can be taught to some, I don’t believe it can be taught to all. Seeking VOC and acting on the information takes humility, curiosity, and a strong desire to serve. In my case, I can’t not do it. Probably you as well. :-)

Hi Karen, great discussion. You touched on a key point in your last reply and in your article. “Seeking VOC and acting on the information takes humility, curiosity, and a strong desire to serve. In my case, I can’t not do it.” Making the effort to go see “seeking VOC” and responding to those “thick data” points, drives the enthusiasm and influences the organisation to make the difference. But the big question is, how many are willing to come down from their ivory towers and MBWA??? As long as the bottom line is good, we doing our jobs well :-).

Drucker said: “Efficiency is doing things right; effectiveness is doing the right things.”, and that can only be achieved by knowing the customer.

Thank you for your comment, Gary. Yes, that is the $6M question: how many leaders are interested in learning how to lead more effectively? I would add that “going to the Gemba” is fairly different than MBWA. Far more purposeful.

Yep they want high scores not the insights from customers.

High scores (often) = better executive bonuses, so don’t rock the boat.

There is so much in this post that is correct.

Done correctly, a mix of qualitative and quantitative insights can deliver true value and insight into what customers want. .

One project I ran as a marketing manager “discovered” that we were too cheap by 100%, that of the 23 (yes 23) benefits we listed only 4 were valued. ( clue: if we don’t buy after hearing these 4 we ain’t going to buy). Finally we really value the service but you don’t remind us often enough of it. We also understood some customers wanted a premium product for which they would pay more.

Action: we doubled our price, simplified our sales messages and shortened the sales pitch, introduced a premium service. Ditched our 3 yr services ( which meant we didn’t talk to you for 3 years) in favour of the older 1 year policy that drove an annual conversation. This annual conversation meant we had to remind you we were still there and then process a bill for you.

Therefore the annual conversations cost more but guess what? Yes that’s right the customers stayted longer and so the lifetime length and values of the customer rose.

Result: the customer base that took 20 years to build, we doubled that in 2.5 years.

Now if such metrics as customer lifetime (length + value) and customer spend were reported as much as other metrics then maybe this could be moved forward.

Don’t get me started on NPS!

Hi Mark. Thank you for your comments. Congratulations for finding the Lean thinking way to double your customer base! And, yes, don’t get me started on NPS! :-)

by Mark Graban

Hotels and hospitals often put a lot of effort into begging for scores and trying to influence the patient by using the phrase “excellent care” over and over again. Maybe they’d be better off actually putting that effort into providing better service!!